… / Erkenning / Formele erkenning / Zweden, resolutie van het Parlement

Zweden, resolutie van het Parlement

[11 maart 2010]

Motion 2008/09:U332 Folkmordet 1915 på armenier, assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och pontiska greker

av Hans Linde m.fl. (v, mp, kd, s, fp)

Folkmordet 1915 på armenier, assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och pontiska greker

1. Förslag till riksdagsbeslut

Riksdagen tillkännager för regeringen som sin mening vad som anförs i motionen om att Sverige ska erkänna folkmordet 1915 på armenier, assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och pontiska greker.

Riksdagen tillkännager för regeringen som sin mening vad som anförs i motionen om att Sverige bör verka inom EU och FN för ett internationellt erkännande av folkmordet 1915 på armenier, assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och pontiska greker.

Riksdagen tillkännager för regeringen som sin mening vad som anförs i motionen om att Sverige bör verka för att Turkiet erkänner folkmordet 1915 på armenier, assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och pontiska greker.

2. Bakgrund

Forum för levande historia är en myndighet som har uppdraget att – med utgångspunkt i Förintelsen – arbeta med frågor som rör tolerans, demokrati och mänskliga rättigheter. Genom att belysa de mörkaste delarna av mänsklighetens historia vill vi påverka framtiden.

Så lyder beskrivningen av en myndighet som arbetar på svenska regeringens uppdrag och utbildar om bl.a. folkmordet 1915. Historiens läxa är en av hörnstenarna i dagens demokratier där man har lärt sig av sina misstag, och genom förebyggande av upprepningar av tidigare fel strävar man mot en bättre framtid. Men ett förebyggande av framtida felsteg, i synnerhet om dessa är kända från historien, kan inte tillämpas om man inte öppet erkänner begångna felsteg. Historierevisionism är därför ett farligt verktyg för underlättandet av upprepning av historiens mörka sidor.

Folkmordet 1915 drabbade främst armenier, assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och pontiska greker men kom senare även att drabba andra minoriteter. Det var drömmen om ett stort turkiskt rike, Storturan, som föranledde de turkiska ledarna att vilja etniskt homogenisera spillrorna efter osmanska rikets sönderfall vid 1800-talets sekelskifte. Detta åstadkoms i skydd av det pågående världskriget då imperiets armeniska, assyrisk/syrianska/kaldéiska och pontisk-grekiska befolkning så gott som förintades helt. Forskarna uppskattar att ca 1.500.000 armenier, 250.000–500.000 assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och ca 350.000 pontiska greker dödades eller försvann.

Under den korta tid som efterföljde Turkiets nederlag år 1918 fram till den turkiska nationalistiska rörelsen, ledd av Mustafa Kemal, diskuterades folkmordet öppet. Politiska och militära ledare ställdes inför rätta, anklagade för “krigsbrott” och “begångna brott mot mänskligheten”. Flera befanns skyldiga och dömdes till döden eller fängelse. Under dessa rättegångar uppdagades horribla detaljer om förföljelserna av minoriteterna i det osmanska imperiet. Turkiet gick således igenom en fas lik den som Tyskland upplevde efter andra världskriget. Processen varade dock inte länge. Uppkomsten av den turkiska nationella rörelsen och upplösningen av sultanatet ledde till att rättegångarna avbröts och att de flesta av de anklagade frigavs. Så gott som hela den återstående kristna befolkningen – armenier, assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och pontiska greker – fördrevs från områden de bebott i tusentals år.

3. FN:s folkmordskonvention 1948, Europaparlamentet och officiella erkännanden

Raphael Lemkin, den polsk-judiske advokaten som myntade begreppet “genocide” (folkmord) under 1940-talet och var upphovsman till FN-konventionen om förebyggande och bestraffning av folkmordsbrott, var väl medveten om folkmordet 1915 och den internationella gemenskapens misslyckande att ingripa. Hans bearbetning av definitionen fastställdes i FN:s konvention som lyder enligt följande:

Artikel 2) I denna konvention innebär folkmord någon av följande handlingar med avsikt att helt eller delvis förinta en nationell, etnisk, ras eller religiös grupp genom att

– döda medlemmar ur gruppen;

– orsaka allvarlig kroppslig eller mental skada hos gruppens medlemmar;

– avsiktligt påverka gruppens levnadsförhållanden för att, helt eller delvis, orsaka dess fysiska förintande;

– påtvinga åtgärder avseende förhindrandet av födslar inom gruppen;

– tvångsförflytta gruppens barn till en annan grupp.

Vidare gäller att dagens FN-konvention från 1948 inte är någon ny lagstiftning utan endast ett fastställande av existerande internationella lagar om “brott mot mänskligheten” som angavs i Sèvresavtalets artikel 230 (1920). än viktigare är FN:s konvention om icke-tillämpbarheten av lagstadgade begränsningar för krigsbrott och brott mot mänskligheten (Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity), antagen den 26 november 1968, i kraft sedan den 11 november 1970, vilket fastställer dess retroaktiva och icke-preskriberbara natur. Av detta skäl betecknas både massakrerna i osmanska riket och Förintelsen som fall av folkmord enligt FN-konventionen trots att båda ägde rum innan konventionens tillkomst.

Under FN:s historia har två stora studier/rapporter förrättats om brottet folkmord. Den första är den s.k. Ruhashyankikorapporten från 1978 och den andra är Whitaker-rapporten, sammanställd av Benjamin Whitaker från år 1985 (Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights, Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, Thirty-eighth session, Item 4 of the provisional agenda, E/CN.4/Sub.2/ 1985/6).

Folkmordet 1915 nämns på flera platser som exempel på begångna folkmord under 1900-talet. Rapporten klubbades igenom i en underkommitté till FN:s kommitté för mänskliga rättigheter med rösterna 14 mot 1 (fyra nedlagda röster) i augusti 1985. Den 18 juni 1987 erkände Europaparlamentet officiellt folkmordet på armenierna. Sedan 1965, dvs. folkmordets 50-årsdag, har flera länder och organisationer officiellt erkänt folkmordet 1915, bl.a. Uruguay (1965), Cypern (1982), Ryssland (1995), Grekland (1996), Libanon (1997), Belgien (1998), Frankrike (1998), Italien (2000), Vatikanstaten (2000), Schweiz (2003), Argentina (2003), Kanada (2004), Slovakien (2004), Nederländerna (2004), Polen (2005), Venezuela (2005), Tyskland (2005), Litauen (2005) och Chile (2007).

4. Forskningen om folkmordet 1915 och svensk vetskap

Efter Förintelsen betraktas folkmordet 1915 som det näst mest studerade fallet i modern tid. I dag existerar en bred och tvärvetenskaplig konsensus hos en överväldigande majoritet av folkmordsforskarna att massakrerna i det osmanska riket, under första världskriget, utgjorde ett folkmord som av forskarna kallas för “folkmordsprototypen” (medan Förintelsen kallas för “folkmordsparadigmet”). Internationella Föreningen för Folkmordsforskare (International Association of Genocide Scholars, IAGS), en oberoende världsledande och tvärvetenskaplig auktoritet inom området, har vid flera tillfällen fastslagit en konsensus i denna fråga, nämligen: 13 juni 1997, 13 juni 2005, 5 oktober 2007 och 23 april 2008. Resolutionstexten från den 13 juli 2007 lyder enligt följande:

“Medan förnekandet av folkmord anses allmänt som sista steget i folkmord och skrinlägger bestraffningen av folkmordets förövare och bevisligen breder vägen för framtida folkmord;

Medan det osmanska folkmordet mot minoritetsbefolkningen under och efter första världskriget anges allmänt som ett folkmord endast mot armenierna, med litet erkännande av de kvalitativt likvärdiga folkmorden mot andra kristna minoriteter i det osmanska imperiet;

Låt det klargöras att det är övertygelsen hos den Internationella Föreningen för Folkmordsforskare att den osmanska kampanjen mot kristna minoriteter i imperiet mellan 1914 och 1923 utgjorde ett folkmord mot armenier, assyrier och pontiska och anatoliska greker.

Låt det klargöras vidare att Föreningen kallar på Turkiets regering att erkänna folkmordet mot dessa grupper, att utfärda en officiell ursäkt och åtaga snara och meningsfulla steg mot upprättelse.”

Den 8 juni undertecknade ett sextiotal världsledande folkmordsexperter en appell riktad mot riksdagens ledamöter där man avfärdade påståenden om oenighet bland forskare beträffande folkmordet 1915. Forskningen måste fortsätta och både Turkiet och omvärlden måste säkra möjligheten till en öppen, oberoende och ostörd atmosfär, bl.a. genom att Turkiet måste ge full tillgång till sina arkiv såväl som att tillåta liknande diskussioner utan att forskare, författare, journalister och publicister riskerar åtal för att påtala folkmordets verklighet.

Ny forskning vid Uppsala universitet vittnar även om en gedigen svensk kunskap om folkmordet 1915. Svenska UD och generalstaben var väl underrättade om den pågående utrotningen via rapporter som Sveriges ambassadör Per Gustaf August Cosswa Anckarsvärd och den svenska militärattachén Einar af Wirsén (båda stationerade i Konstantinopel) skickade till Stockholm. Bland annat kan man läsa följande:

Anckarsvärd, 6 juli 1915: “Herr Minister, Förföljelserna mot armenierna hafva antagit hårresande proportioner och allt tyder på att ungturkarne vilja begagna tillfället, då af olika skäl ingen effektiv påtryckning utifrån behöfver befaras, för att en gång för alla göra slut på den armeniska frågan. Sättet härför är enkelt nog och består i den armeniska nationens utrotande.”

Anckarsvärd, 22 juli 1915: “Det är icke blott armenierna utan äfven Turkiets undersåtar af grekisk nationalitet som f.n. äro utsatta för svåra förföljelser... Det kunde enligt hr. Tsamados [grekisk chargé d'affaires] icke vara fråga om annat än ett utrotningskrig mot den grekiska nationen i Turkiet...”

Anckarsvärd, 2 september 1915: “De sex s.k. armeniska vilayeten lära vara totalt rensade från åtminstone armenisk-katolska armenier ... Det är uppenbart att turkarna söka begagna tillfället nu under kriget för att utplåna den armeniska nationen, så att när freden kommer ingen armenisk fråga längre existerar.”

Wirsén, 13 maj 1916: “Hälsotillståndet i Irak är förfärande. Fläcktyfusen kräfver talrika offer. Armenierförföljelserna hafva i hög grad bidragit till sjukdomens spridande, emedan de utdrifna i hundratusental dött af hunger och umbäranden längs vägarna.”

Anckarsvärd, 5 januari 1917: “Tillståndet kunde dock varit ett helt annat, om nämligen Turkiet följt centralmakternas råd att till dem överlåta äfven den inre organisationen af provianterings- o. d. frågor ... Värre än detta är emellertid utrotandet af armenierna, som kanske kunnat förhindras, om tyska rådgifvare i tid fått samma makt öfver den civila förvaltningen som de tyska officerarne faktiskt utöfva öfver här och flotta.”

Envoyé Ahlgren, 20 augusti 1917: “Dyrtiden stegras alltjämnt... Den har flera orsaker:... och slutligen produktionens starka aftagande på grund af minskad arbetskraft, orsakad dels genom mobiliseringen dels ock genom utrotandet af den armeniska rasen”.

I sina memoarer “Minnen från Fred och Krig” (1942), tillägnade Wirsén ett helt kapitel åt folkmordet. I “Mordet på en nation” skriver Wirsén att:

“[deportationerna] hade officiellt till mål att flytta hela den armeniska befolkningen till steppområden i norra Mesopotamien och i Syrien, men i verkligheten avsågo de att utrota armenierna... Förintandet av den armeniska nationen i Mindre Asien måste uppröra alla mänskliga känslor. Det hör utan tvivel till de största brott som under senare århundraden begåtts. Det sätt på vilket det armeniska problemet löstes var hårresande.”

Utöver dessa finns det flertalet ögonvittnesberättelser som missionärer och fältarbetare såsom Alma Johansson, Maria Anholm, Lars Erik Högberg, E. John Larson, Olga Moberg, Per Pehrsson m.fl. publicerade. Hjalmar Branting var den allra första personen som långt innan Lemkin använde begreppet folkmord när han den 26 mars 1917 kallade förföljelserna av armenierna för ett “organiserat och systematiskt folkmord, värre än vad vi någonsin sett maken till i Europa”.

Ett erkännande av folkmordet 1915 är inte endast viktigt för att få upprättelse för de drabbade folkgrupperna och de minoriteter som finns kvar i Turkiet utan även för främjandet av Turkiets utveckling. Turkiet kan inte bli en bättre demokrati om sanningen om dess förgångna förnekas. Den armeniske journalisten Hrant Dink mördades för att ha uttalat sig öppet om folkmordet och flera andra har åtalats för samma sak enligt den ökända paragraf 301.

Turkiska regeringens senaste ändring av lagen är rent kosmetiska och innebär inte några som helst förändringar. Det sägs ibland att historien ska skrivas av historiker, och det ställer vi oss fullständigt bakom. Men det är politikers ansvar att förhålla sig till historiska faktum och historikernas forskning. Vidare bör ett svenskt erkännande av sanning och historiska faktum inte innebära något hinder för vare sig reformarbetet i Turkiet eller Turkiets EU-förhandlingar. Utifrån vad vi ovan anfört anser vi att Sverige bör erkänna folkmordet 1915 på armenier, assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och pontiska greker. Detta bör riksdagen som sin mening ge regeringen till känna.

Vi anser vidare att Sverige bör verka internationellt inom ramen för EU och FN för ett internationellt erkännande av folkmordet 1915 på armenier, assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och pontiska greker. Detta bör riksdagen som sin mening ge regeringen till känna.

Så länge länder som Sverige inte konfronterar Turkiet med sanningen och det faktaunderlag som finns till hands kan Turkiet inte komma vidare på sin väg mot ett öppnare samhälle, en bättre demokrati och fullt ut öppna möjligheterna för ett medlemskap i EU. Sverige bör därför verka för att Turkiet erkänner folkmordet 1915 på armenier, assyrier/syrianer/kaldéer och pontiska greker. Detta bör riksdagen som sin mening ge regeringen till känna.

Stockholm den 2 oktober 2008

Hans Linde (v)

Max Andersson (mp)

Bodil Ceballos (mp)

Esabelle Dingizian (mp)

Annelie Enochson (kd)

Yilmaz Kerimo (s)

Kalle Larsson (v)

Helena Leander (mp)

Fredrik Malm (fp)

Lars Ohly (v)

Nikos Papadopoulos (s)

Mats Pertoft (mp)

Lennart Sacrédeus (kd)

Alice Åström (v)

Christopher Ödmann (mp)

Engelse vertaling:

Motion to the Riksdag 2008/09:U332

By Hans Linde, etc. (Left Party, Green Party, Christian Democrats, Social Democratic Party and Liberal Party)

Genocide of Armenians, Assyrians/Syriacs/Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks in 1915

1. Proposal for a decision by the Riksdag

The Riksdag (Swedish Parliament) announces to the Government what is stated in the motion regarding the fact that Sweden should recognise as an act of genocide the killing of Armenians, Assyrians/Syrians/Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks.

The Riksdag announces to the Government what is stated in the motion regarding the fact that Sweden should work in the EU and the UN towards international recognition as an act of genocide of the killing of Armenians, Assyrians/Syrians/Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks.

The Riksdag announces to the Government what is stated in the motion regarding the fact that Sweden should work towards Turkey’s recognition as an act of genocide of the killing of Armenians, Assyrians/Syrians/Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks.

2. Background

The Living History Forum is a public authority entrusted with the task of working with issues concerning tolerance, democracy and human rights, against the background of the Holocaust. By illuminating one of the darkest parts of the history of humanity, we want to influence the future.

This is the description given by an authority working at the request of the Government to inform and educate on such subjects as the genocide of 1915. The lesson of history is one of the cornerstones of the democracies of today where we have learnt from our mistakes, and by preventing the repetition of previous mistakes, we are striving for a better future. However, the prevention of wrong steps being taken in the future, especially when we are already familiar with these from history, cannot be carried out unless such errors that have already been made are openly recognised. Revisionism is therefore a dangerous tool when it comes to facilitating repetition of the darker sides of history.

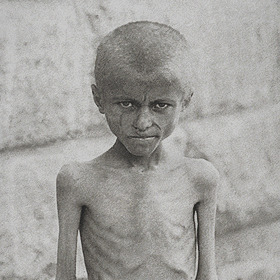

The genocide of 1915 mainly affected Armenians, Assyrians/Syriacs/Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks, but later it was also to affect other minorities. It was the dream of a great Turkish state, Greater Turan, which encouraged the Turkish leaders to ethnically homogenise what was left of the scattered remains of the Ottoman Empire following its collapse at the turn of the previous century. This was achieved under the cover of the world war which was raging at the time, and the Armenian, Assyrian/Syriac/Chaldean and Pontic Greek population of the empire was virtually annihilated. Researchers estimate that approx. 1,500,000 Armenians, 250,000 – 500,000 Assyrians/Syriacs/Chaldeans and approx. 350,000 Pontic Greeks were killed or disappeared.

During the short period following the defeat of Turkey in 1918 until the time of the Turkish national movement, under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, the genocide was discussed openly. Political and military leaders were put on trial, accused of “war crimes” and “crimes committed against humanity”. Many were found guilty and sentenced to death or imprisonment. During these trials, horrible details were revealed about the persecution of minorities in the Ottoman Empire. Turkey thus went through a phase similar to the one experienced by Germany after the second world war. However, the process was to be short-lived. The emergence of the Turkish national movement and the dissolution of the Sultanate led to the discontinuation of the trials and the majority of the accused were set free. Virtually the whole of the remaining Christian population – Armenians, Assyrians/Syriacs/Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks – were expelled from areas they had lived in for thousands of years.

3. UN Genocide Convention 1948, the European Parliament and Official Recognition

Raphael Lemkin, the Polish Jewish lawyer who coined the term “genocide” in the 1940s and was the originator of the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was well aware of the genocide of 1915 and the failure of the international community to intervene. His version of the definition was adopted in the UN Convention and it reads as follows:

Article 2) In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

– Killing members of the group;

– Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

– Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

– Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

– Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Furthermore, it is established that the current UN Convention from 1948 does not constitute new legislation, but merely a ratification of existing interna-tional laws on “crimes against humanity” as stated in the Treaty of Sèvres, Article 230 (1920). Even more important is the UN Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity, adopted on 26 November 1968 and in force since 11 November 1970, which establishes its retroactivity and bars such crimes from falling under any form of statutory limitation. For this reason, both of the massacres in the Ottoman Empire and those of the Holocaust are designated as cases of genocide according to the UN Convention, despite the fact that they both took place before the Convention originated.

During the history of the UN, two major studies/reports have been carried out on the crime of genocide. The first is the Ruhashyankiko Report from 1978, and the second is the Whitaker Report, compiled by Benjamin Whitaker in 1985 (Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights, Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, Thirty-eighth session, Item 4 of the provisional agenda, E/CN.4/Sub.2/ 1985/6).

The 1915 genocide is mentioned in several places as an example of an act of genocide committed during the 20th century. The report was approved in a sub-commission to the UN Commission on Human Rights with 14 votes in favour and one against (and four abstentions) in August 1985. On 18 June 1987, the European Parliament officially recognised the act of genocide committed against the Armenians. Since 1965, that is the fiftieth anniversary of the genocide, several countries and organisations have officially recognised the genocide of 1915, including Uruguay (1965), Cyprus (1982), Russia (1995), Greece (1996), Lebanon (1997), Belgium (1998), France (1998), Italy (2000), the Vatican (2000), Switzerland (2003), Argentina (2003), Canada (2004), Slovakia (2004), the Netherlands (2004), Poland (2005), Venezuela (2005), Germany (2005), Lithuania (2005) and Chile (2007).

4. Research on the 1915 genocide, and Swedish awareness of it

After the Holocaust, the 1915 genocide is regarded as the most studied case in the modern period. Today there is a broad, cross-disciplinary consensus among an overwhelming majority of genocide scholars that the massacres in the Ottoman Empire during the first world war constitute genocide. It is regarded as the “genocide prototype” (while the Holocaust is referred to as the “genocide paradigm”). On a number of occasions the International Association of Genocide Scholars, IAGS, an independent, cross-disciplinary, world-leading authority in this field, has confirmed this consensus, namely on 13 June 1997, 13 June 2005, 5 October 2007, and 23 April 2008. The wording of the resolution of 13 July 2007 is as follows:

“WHEREAS the denial of genocide is widely recognised as the final stage of genocide, enshrining impunity for the perpetrators of genocide and demonstrably paving the way for future genocides;

WHEREAS the Ottoman genocide against minority populations during and following the First World War is usually depicted as a genocide against Armenians, with little recognition of the qualitatively similar genocides against other Christian minorities in the Ottoman Empire;

BE IT RESOLVED that it is the conviction of the International Associa-tion of Genocide Scholars that the Ottoman campaign against Christian minorities of the Empire between 1914 and 1923 constituted a genocide against Armenians, Assyrians, and Pontian and Anatolian Greeks.

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that the Association calls upon the government of Turkey to acknowledge the genocides against these populations, to issue a formal apology and take prompt and meaningful steps towards restitution.”

On 8 June some sixty eminent genocide experts signed an appeal to the members of the Riksdag dismissing claims of disunity among scholars regarding the 1915 genocide. Research must continue and both Turkey and other countries must ensure the possibility of an open, independent and impartial atmosphere for conducting this research, by means such as Turkey giving full access to its archives and permitting similar discussions without researchers, authors, journalists and publicists risking prosecution for recognising and criticising the reality of the genocide.

Recent research at Uppsala University also testifies to the fact that there was detailed knowledge of the 1915 genocide in Sweden. The Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the General Staff were well informed of the ongoing extermination via reports sent to Stockholm by the Swedish Ambassador Per Gustav August Cosswa Anckarsvärd and the Swedish Military Attaché Einar af Wirsén (both stationed in Constantinople). These include the following extracts:

Anckarsvärd, 6 July 1915: “Your Excellency! Persecutions of the Armenians have assumed hair-raising proportions and everything indicates that, as for various reasons no effective external pressure need be feared, the Young Turks wish to exploit the opportunity to once and for all put an end to the Armenian question. Their method is quite simple. It consists of exterminating the Armenian nation.”

Anckarsvärd, 22 July 1915: “It is not only Armenians, but also Turkish subjects of Greek nationality who are being persecuted with extreme severity ... According to Mr. Tsamados [the Greek chargé d'affaires], what is at issue is nothing less than a war of extermination against the Greek nation in Turkey ...”

Anckarsvärd, 2 September 1915: “The six Armenian vilayeten [provinces] now appear to be completely cleansed of at least Armenian-Catholic Armenians ... It is clear that the Turks are seeking to exploit the opportunity presently offered by the war to obliterate the Armenian nation, so that when peace comes there will no longer be any Armenian question.”

Wirsén, 13 May 1916: “The health situation in Iraq is appalling. Typhus fever is claiming numerous victims. The Armenian persecutions have greatly contributed to the spread of the disease, as those expelled have died of hunger and deprivation in their hundreds of thousands along the roads.”

Anckarsvärd, 5 January 1917: “The situation could have been completely different, however, if Turkey had followed the advice of the Central Powers and transferred to them the internal organisation of supplies and other matters ... Worse than this, however, is the extermination of the Armenians, which it may have been possible to prevent if the same power that German officers de facto exercise over the army and navy had been handed over to German advisers in the civil administration.”

Envoy Ahlgren, 20 August 1917: “Shortages and high prices are still on the rise ... There are several reasons for this ... lastly: the great decrease in production caused by a reduced supply of labour, which is partly due to mobilisation and partly due to the extermination of the Armenian race”.

In his memoirs “Memories of Peace and War” (1942) Wirsén devoted an entire chapter to the genocide. In “The Murder of a Nation” Wirsén writes that

“Officially, these [deportations] had the objective of moving the whole Armenian population to the steppe regions of northern Mesopotamia and Syria, but in reality the intention was to exterminate the Armenians ... The annihilation of the Armenian nation in Asia Minor is an affront to all human feeling. This is without doubt one of the greatest crimes perpetrated in recent centuries. The manner in which the Armenian problem has been resolved is hair-raising.”

In addition, there are eye-witness reports published by missionaries and field workers like Alma Johansson, Maria Anholm, Högberg, E. John Larsson, Olga Moberg, Per Pehrsson and others. Hjalmar Branting was the very first person to use the term genocide when, long before Lemkin, on 26 March 1917, he called the persecutions of the Armenians “organised and systematic genocide, worse than anything we have ever seen in Europe”.

Recognition of the 1915 genocide is not only important for bringing redress to the directly affected ethnic groups and the minorities that are still living in Turkey, but also for assisting the development of Turkey itself. Turkey cannot become a better democracy if the truth about its past is denied.

The Armenian reporter Hrant Dink was murdered for having openly expressed himself regarding the genocide, and several others have been prosecuted for the same thing under the infamous Clause 301. The Turkish Government's most recent amendments to the law are purely cosmetic and do not entail the slightest change. It is sometimes said that history should be written by historians, and we fully agree. However, politicians have a responsibility to take into account historical facts and historical research.

Further, Swedish recognition of the truth and historical facts should not constitute any obstacles either to reform efforts in Turkey or to Turkey's EU negotiations. On the basis of what we have stated above we consider that Sweden should recognise the 1915 genocide of Armenians, Assyrians / Syrians / Chaldeans, and Pontic Greeks. The Riksdag should announce this to the Government as its considered opinion.

We further consider that Sweden should act internationally in the framework of the EU and the UN to gain international recognition of the 1915 genocide of Armenians, Assyrians / Syrians / Chaldeans, and Pontic Greeks. The Riksdag should announce this to the Government as its considered opinion.

As long as countries like Sweden do not confront Turkey with the truth and the factual evidence available, Turkey will not be able to proceed any further on its path towards a more open society and better democracy, or fully develop its chances of membership in the EU. For this reason Sweden should act for Turkish recognition of the 1915 genocide of Armenians, Assyrians / Syrians / Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks. The Riksdag should announce this to the Government as its considered opinion.

Stockholm, 2 October 2008

Hans Linde (Left)

Max Andersson (Green)

Bodil Ceballos (Green)

Esabelle Dingizian (Green)

Annelie Enochson (Christian Democrat)

Yilmaz Kerimo (Social Democrat)

Kalle Larsson (Left)

Helena Leander (Green)

Fredrik Malm (Liberal)

Lars Ohly (Left)

Nikos Papadopoulos (Social Democrat)

Mats Pertoft (Green)

Lennart Sacrédeus (Christian Democrat)

Alice Åström (Left)

Christopher Ödmann (Green)